- Zach Edey posted an easy double-double in Summer League debut. Here’s why he’ll succeed in NBAPosted 2 weeks ago

- What will we most remember these champion Boston Celtics for?Posted 1 month ago

- After long, seven-year road filled with excruciating losses, Celtics’ coast to NBA title felt ‘surreal’Posted 1 month ago

- South Florida men’s basketball is on an unbelievable heater– but also still on the bubblePosted 5 months ago

- Kobe Bufkin is balling out for Atlanta Hawks’ G League team. When will he be called up to NBA?Posted 6 months ago

- Former Knicks guards Immanuel Quickley, RJ Barrett may yet prove Raptors won the OG Anunoby tradePosted 7 months ago

- Rebounding savant Oscar Tshiebwe finally gets NBA chance he’s deserved for yearsPosted 7 months ago

- Is Tyrese Maxey vs. Tyrese Haliburton the next great NBA guard rivalry?Posted 8 months ago

- The Detroit Pistons are going to be a problem in a few yearsPosted 9 months ago

- March Madness hero, ex-Fairleigh Dickinson guard Demetre Roberts joins Austin Spurs’ G League training camp rosterPosted 9 months ago

Texas Western, the first All-Black starting team in an NCAA tournament, changed the landscape of college basketball, and continues to be commemorated 55 years later

- Updated: March 4, 2021

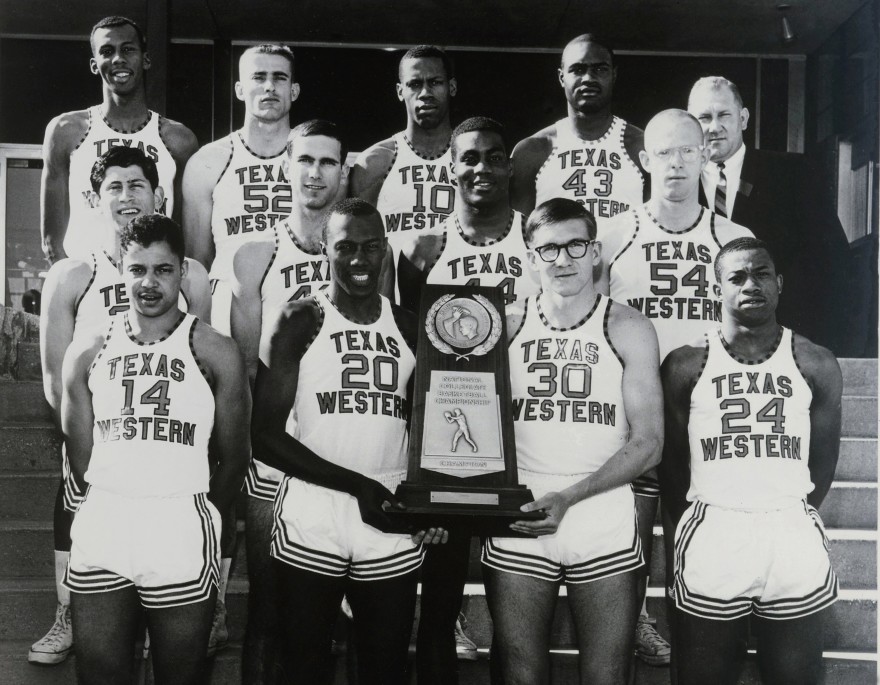

Front row (L to R); BOBBY JOE HILL, ORSTEN ARTIS, Togo Railey, WILLLIE WORSLEY.

Middle row: David Palacio, Dick Myers, HARRY FLOURNEY, Louis Boudin.

Back row: NEVIL SHED, Jerry Arnstrong, WILLIE CAGER, DAVID LATTIN, Coach Don Haskins.

(UTEP photo)

By Joel Alderman

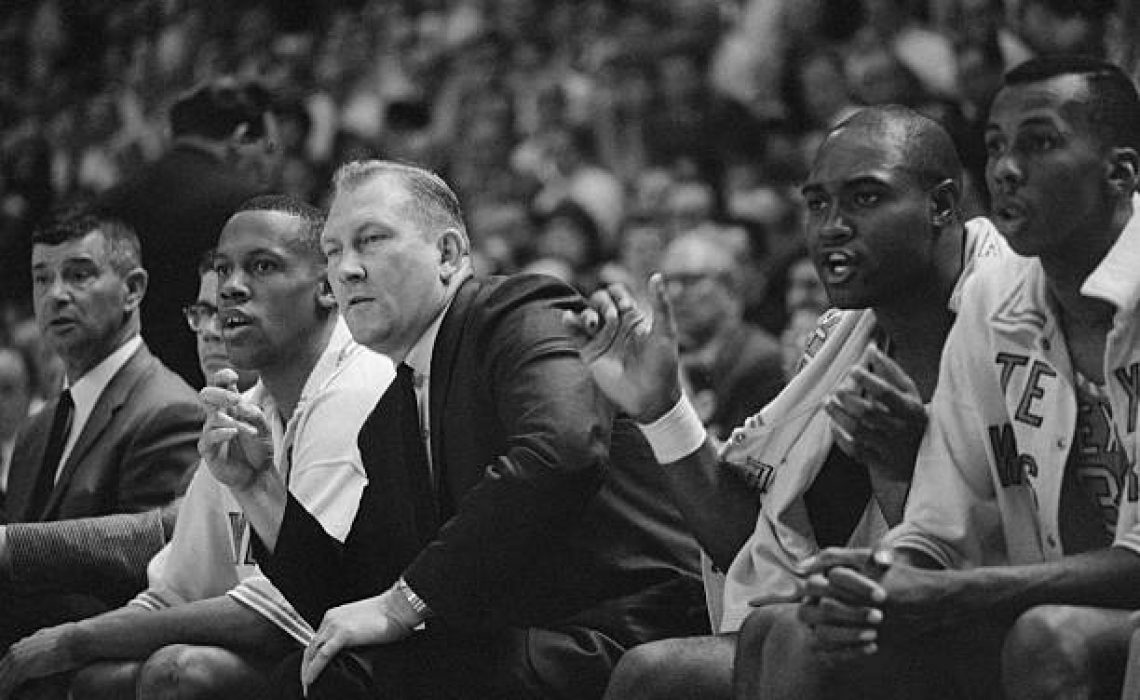

Although the annual Black History Month has ended, a college basketball game that took place exactly 55 years ago this March 19th will continue indefinitely to be commemorated. Five African Americans took their positions on the court for Texas Western (now the Univ. of Texas at El Paso) to tip-off against the all-caucasian Univ. of Kentucky in the championship game of the NCAA tournament. Two more entered off the bench.

“What a piece of history. If basketball ever took a turn, that was it,” said Nolan Richardson, the Hall of Fame coach of the Arkansas 1994 NCAA champions, who is black and played for Coach Haskins at Texas Western, although not in 1966.

Today it is the norm to see a diverse racial makeup on college basketball teams. However, before 1966 a college had never put five African Americans in the opening lineup, not only in an NCAA championship game but in ANY game. Texas Western, under coach Haskins, did both that season.

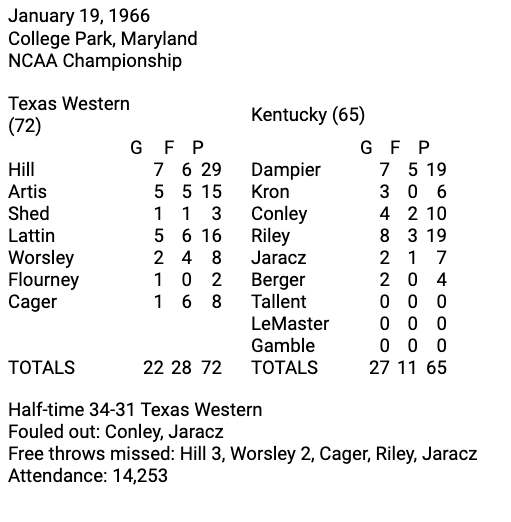

On March 19, 1966, Kentucky was the nation’s top-ranked team, and Texas Western number three. Each of them went into the title game in the Univ. of Maryland’s Cole Field House with identical 27-1 records after dropping the last game of the regular season.

The Wildcats received a first-round bye, but Texas Western had to go through four rounds of tournament play and win one in overtime and another in double overtime before facing the Wildcats. The Texas institution, hardly known nationally, was originally a small engineering school of mining in El Paso, just across the Mexican border.

A stunning and significant milestone

An eight-point underdog, the Texas Western 72-65 upset that Saturday night over Kentucky, coached by the legendary Adolph Rupp, stunned the college basketball world and had a lasting impact on the future of intercollegiate athletics. It did not need a Black History Month for recognition.

Pat Riley, a junior, was the starting center for Kentucky

“There was a certain style of play whites expected from blacks,” said Perry Wallace, who a year later at Vanderbilt became the first black player in the Southeastern Conference and after graduation a prominent lawyer. “N***** ball they used to call it,” and he said “Whites then thought that if you put five blacks on the court at the same time, they would somehow revert to their native impulses.” (Chris Surovick; Bleacher Report.com, 3/19/2010).

Pat Riley was a junior at Kentucky and played the center position. Riley later became a New York Knick player, NBA coach, and team executive, which he still is for the Miami Heat. He was quoted in the Bergen Record that “It was one of the most significant games ever played. . . I’m still proud to be part of something that changed the lives of so many people.”

In direct contrast was the not-so-kind comment during the tournament by Rodney (Hot Rod) Hundley, who played at West Virginia and for the Los Lakers and was a television broadcaster for the Utah Jazz. Hundley wisecracked during the 1966 tournament, “They (Texas Western) can do everything with the basketball but sign it.” (John W. Stewart in the Baltimore Sun)

The implication is obvious.

About the players

Rupp’s Runts, as they were called in the media, included future ESPN broadcaster Larry Conley, Louie Dampier, who starred in the old ABA and for a few years in the NBA, and Riley in the pivot position. The roster was not very tall, but quick, and athletic. And, like all of Rupp’s personnel, was always on the go.

In contrast, the Miners played a slow and deliberate style, especially against the Wildcats. Texas Western guard Willie Worsley said after the game, “We played the most intelligent, the most boring, the most disciplined game of them all.”

The Miners’ seven black players, four of whom graduated, all saw action in the contest. Bobby Joe Hill, a 5-foot-10 guard who took scoring honors with 20 points, David Lattin, Orsten Artus, Henry Flourney, Nevil Shedd, Willie Worsley, and Willie Cager, the last two coming in off the bench. In future years Lattin became an executive with a Houston liquor distributor, Artis was a detective sergeant in Gary, Ind., and Bobby Joe Hill a buyer for El Paso Natural Gas Co. The four white and one Hispanic on the team did not play that night, which was the plan of Haskins going in.

Sadly, we must report that three of those seven African Americans basketball pioneers have passed on- Bobby Joe Hill, Orsten Artis, and Harry Flourney. The two head coaches have also died.

Before the game began Haskins informed his players that Rupp, often referred to as the “Baron of the Bluegrass” or simply as Baron Rupp, had vowed five blacks would never beat his team. Rupp may have actually said that or Hoskins used it as motivation.

The Texas starters, all black, were Bobby Joe Hill, David Lattin, Orsten Artis, Nevil Shedd and Harry Flourney.

Opposite them were Larry Conley, Pat Riley, Thad Jaracz, Louie Dampier and Tommy Kroon. They were all Caucasian.

High in the bleachers, Kentucky fans waved a Confederate flag. The contest was ready to start.

The Miners made an early statement

On the Miners’ second possession, center Lattin took a pass from Hill and dunked over Riley. Referee Steve Honzo called a foul on Riley. Years later Thornton Jenkins, who was the trail official (there were just two then) recalls that dunk was the “dominating point of the game.”

With 10:18 left in the first half Texas Western was ahead 10-9 by the margin of a Nevil Shedd free throw and NEVER TRAILED AGAIN IN THE GAME. Kentucky’s only leads came in the first 10 minutes, at 1-0 and 7-3. Of course, this was contrary to what would be drummed up in Hollywood, which we will get to later.

Throughout the game Kentucky was held to a 38.6 field goal average, its lowest of the season. Texas Western scored on 44.9 percent of their shots, which was about their norm.

Right after Shedd’s foul shot, Hill stole the ball from Tommy Kron and raced back for an easy layup. Seconds later he did the same to the other guard, Louie Dampier. and again laid the ball up for two points. Those two baskets within 10 seconds gave the Miners a five-point bulge at 14-9. They never trailed again (Hollywood please take note).

Rupp jumped up and called timeout. As they were coming off the court, he confronted his two guards about the steals. “You stupid sons of bitches!’ he blurted out within earshot of Eddie Mullins, who was UTEP’s Sports Information Director for nearly forty years. (Frank Fitzpatrick, ESPNClassic.com)

But Rupp did give credit to Hill later for the inevitable turning point of the game. “Hill hurt us – hurt us real bad with those two steals.”

Reilly has described it as “a violent game. I don’t mean there were any fights — but they were desperate, and they were committed, and they were more motivated than we were.”

The Texas team nursed the lead after Hill made those two quick steals. The Miners never trailed again and were in front 34-31 at the half.

With 3-1/2 minutes gone in the second half the lead was just one. Then Orsten Artis and Hill scored six straight points, the margin was up to nine and Western won going away.

His only defeat in an NCAA final haunted Rupp. “(He) carried the memory of that game to his grave,” wrote his biographer, Russell Rice, author of several books about Kentucky hoops. Friends noted that even as he was dying of cancer in a Lexington hospital in 1977, he still bemoaned the loss.

He always blamed it on a flu bug, on inept shooting, on the referees, sometimes even hinting that Texas Western used ineligible players. (Shades of a “stolen” election)

The New York Times coverage of the title game by Gordon S. White, Jr. failed to make any mention of its historic implications. Either the well-known writer did not grasp its significance (which is hard to believe) or he was told by editors to report it as just a basketball game and leave out the social part. Actually, none of the articles I have seen delved into race. But if any paper would have, it is strange that the Times did not touch it. That is completely opposite to what we would expect from the Times today.

Was Rupp a racist?

Adolph Rupp was born, raised, and went to college in Kansas. He was said to be a racist, not unlike many with his Kentucky background. The racism charge could never be confirmed and remains controversial.

“I know there have been a lot of people who thought he was a racist. But I think the times can dictate how people act, where you’re brought up, how you’re brought up. If he was a racist, he wasn’t alone in this country. . . that’s a long time ago too. You learn from the past and then you go on.” (Tubby Smith, Chicago Tribune, Nov. 30, 1997)

Said Louie Dampier of Kentucky: “There was nothing racial about that game and it was never mentioned.”

“Glory Road” a good film but not wholly accurate

This story, with several Hollywood factoids (statements that appear to be true but are not), was the basis of the 2006 film “Glory Road” with Josh Lucas starring as the young coach. Before that, Haskins had written a book with the same title and on which the cinema version was based.

The late critic Roger Hebert gave it three stars, and claimed that although college teams had been integrated “there was an informal rule that you never played more than one black player at home, two on the road, or three if you were behind.” Where Hebert heard about that “informal rule” he did not say, but he was not the only one who expressed it.

The late critic Roger Hebert gave it three stars, and claimed that although college teams had been integrated “there was an informal rule that you never played more than one black player at home, two on the road, or three if you were behind.” Where Hebert heard about that “informal rule” he did not say, but he was not the only one who expressed it.

In the closing credits, Riley is seen saying that Haskins and his team wrote the “emancipation proclamation of 1966.” The film was a co-production of Walt Disney Pictures. It won the ESPY award for Best Sports Movie of 2006, which means little since there were so few sports movies then and now.

In case you would like to catch it on the internet, be advised of these fabrications:

1. In the movie version, Kentucky was ahead by eight in the second half, but as noted above the Wildcats never led after Hill’s successive steals in the first half. What the producers had to gain by the fictitious second-half score, I do not know and it diminishes the credibility of the film. I checked on the internet for byline stories and those of the AP and UP. They all confirmed that the Kentucky Wildcats never led in the second half by eight or any number of points. The only times they were in front were 1-0 and 7-3. It got close in the first three minutes of the second half, 39-38 and again at 50-49 with just over eight minutes to play. But the Miners regrouped and had the biggest margin in the game, 68-57, with 3:22 to go.

2. The actor who played Rupp (John Voight) is seen running onto the floor to protest a non-call. But Thornton Jenkins, one of the actual game officials, who died in 2015, could not recall that it ever happened.

3. During a Christmas break scene, Texas Western was said by Hollywood to have a 17-0 record. Nonsense! In 1966 the season-opening games were not permitted to take place before Dec. 1st. No college team, then or now, plays 17 times in less than four weeks.

4. Coach Haskins (John Lucas) remarked in the film that he was glad to have a job offer in “Division 1.” However, the NCAA did not have numbered divisions until 1971. In 1966 there was a “University Division” and a “College Division.”

5. The championship between Texas Western and Kentucky is televised by NBC, we are led to believe. Wrong! The game was carried by Sports Network, which was not a pre-existing network but a company that would sign up stations on a game-by-game basis in the 1950s and 1960s. NBC did not televise the NCAA championship until 1969.

6. Referring to the quarter-final Texas Western-Kansas contest, the “announcer” claimed that the winner would move on to the title game. Wrong again! Texas Western advanced not to the finals but to the semi-finals in which it played Utah.

QUESTION: What does Hollywood gain by going against the record books and facts that can be easily checked?

LESSON: Don’t believe everything you see on the screen.

Kentucky’s first black player is not a nice story

It was not until December of 1970 that a Rupp team first dressed a black player, Tom Payne. Two years later, Payne had left, and was eventually convicted of several rapes. It was not the kind of resume Kentucky needed for one of its former players to have. By then, SEC schools like Auburn and Mississippi had several blacks on their teams.

Final thoughts

“The fact that he was doing something historic by playing five African Americans probably never crossed Don’s mind,” said Haskins’ assistant, Moe Iba, son of Hall of Fame coach Henry Iba. “Hell, he’d have played five kids from Mars if they were his best five players.”

Haskins coached until 1999, and, like Rupp was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall for Fame. Ironically, Haskins was born the same year Rupp started coaching at Kentucky. This was Haskins first season at the helm. Previously he coached the women’s game.

In the last of Rupp’s 1,066 games, March 18, 1972, his Wildcats lost to Florida State 73-54 in the NCAA Mideast Regional finals in Dayton, Ohio.

Kentucky was again all-white.

Florida State started five blacks.

The 1966 all-tournament team:

Louie Dampier, Kentucky 12 years in ABA

Pat Riley, Kentucky

Jerry Chambers (MVP), Utah

Bobby Joe Hill (deceased), Texas Western

Jack Marin, Duke

No longer in the game

Named in article and dates of passing:

Adolph Rupp Dec. 10, 1977

Steve Honzo Aug. 17, 1996

Bobby Joe Hill Dec. 8, 2002

Don Haskins Sept. 7, 2008

Roger Hebert April 4, 2013

“Hot Rod” Hundley March 27, 1915

Thornton Jenkins June 25, 2015

Harry Flournoy Nov. 26, 2016

Orsten Artis Dec. 26, 2017