- Attacking style not the only reason some Tottenham fans will back Ange Postecoglou until the bitter endPosted 5 months ago

- Paris Olympics takeaways: What did Team USA’s crunch-time lineup say about NBA’s hierarchy?Posted 10 months ago

- Zach Edey posted an easy double-double in Summer League debut. Here’s why he’ll succeed in NBAPosted 11 months ago

- What will we most remember these champion Boston Celtics for?Posted 12 months ago

- After long, seven-year road filled with excruciating losses, Celtics’ coast to NBA title felt ‘surreal’Posted 12 months ago

- South Florida men’s basketball is on an unbelievable heater– but also still on the bubblePosted 1 year ago

- Kobe Bufkin is balling out for Atlanta Hawks’ G League team. When will he be called up to NBA?Posted 1 year ago

- Former Knicks guards Immanuel Quickley, RJ Barrett may yet prove Raptors won the OG Anunoby tradePosted 1 year ago

- Rebounding savant Oscar Tshiebwe finally gets NBA chance he’s deserved for yearsPosted 1 year ago

- Is Tyrese Maxey vs. Tyrese Haliburton the next great NBA guard rivalry?Posted 2 years ago

UConn was first college in New England with five African-American starters; one of Dee Rowe’s coaching legacies

- Updated: July 6, 2021

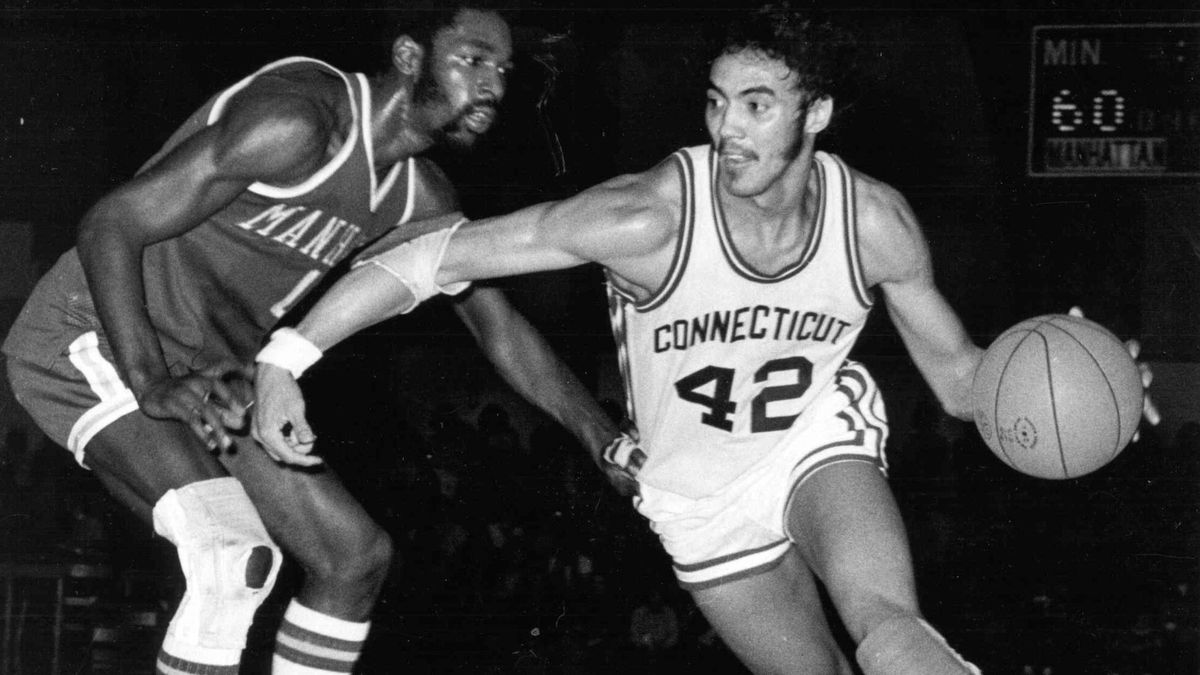

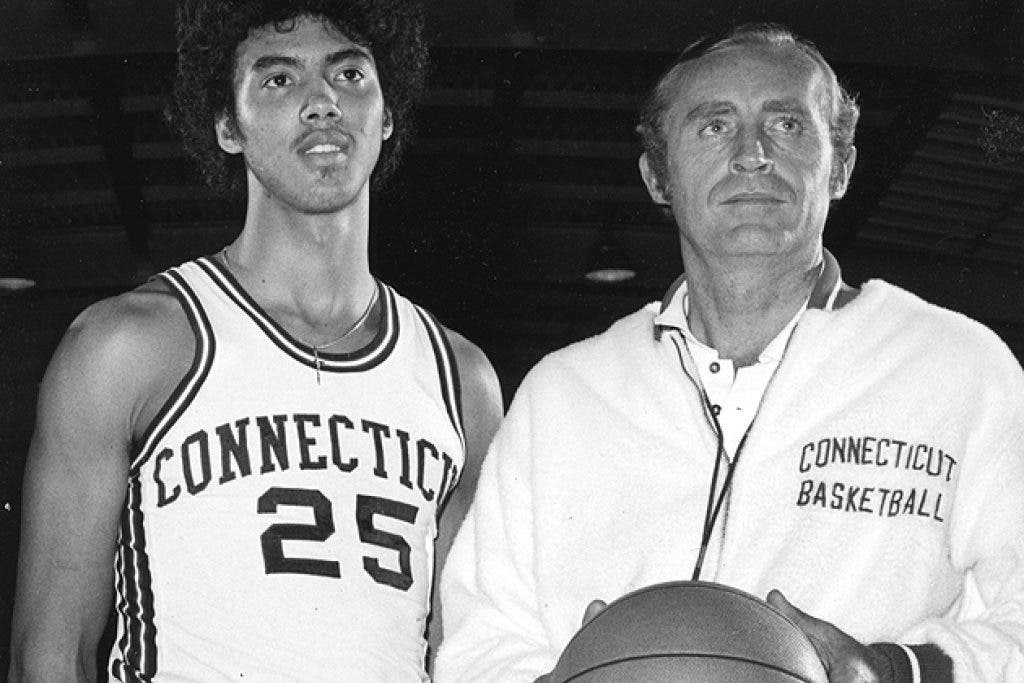

UConn coach Dee Rowe, pictured here with Waterbury’s Tony Hanson, will be remembered for his inclusive spirit when it came to race, and his Huskies fielded the first all-black team in New England.

By Joel Alderman

While researching former University of Connecticut basketball coach Dee Rowe after his passing earlier this year, this writer came across a little-known part of his life. In January of 2016, Karl Lindholm stated in the Addison County Independent, a Rutland VT weekly, that Rowe was the first coach in New England to have an African-American starting five. The comment was reprinted in that paper on Jan. 21, 2021.

He and Rowe were close friends, and Lindholm said Dee had told him that he wished his legacy to be that he helped people not to see color anymore.

Lindholm is a retired professor at Middlebury College and played basketball there when a student. Middlebury is also Rowe’s alma mater and where he coached early in his career and continued to teach a course even while at UConn.

Lindholm recalled that the ‘70s “were a time of tumult, protest, and disorder. Rowe, he wrote, “developed a profound commitment to social justice and racial equality.”

Although not as historic as when all-black Texas Western defeated Kentucky in the finals of the 1966 NCAA tournament, this UConn milestone has a place in college basketball annals, especially relevant in the present era of strong efforts toward racial equality.

Most college programs have had a similar highlight in their basketball histories like the one about which this article is written. It is presented here not to claim that UConn is unique, but because the necessary information has been uncovered, and as a tribute to Rowe. It is also a testimonial to Harrison “Honey” Fitch, Connecticut’s first player and student of color in 1934, when it was the Connecticut State Agricultural College.

Fitch paved the way for the occasion we mark now when UConn first started five African-American players.

To narrow down the particular game it was in required extensive research since we could find nothing published that previously refers to when, where, and against whom. That was not surprising. The media was not attuned to social issues in the 1970s as it is today. Even the Texas Western-Kentucky game did not immediately inspire the significance it later acquired that included the production of a Hollywood movie (“Glory Road”).

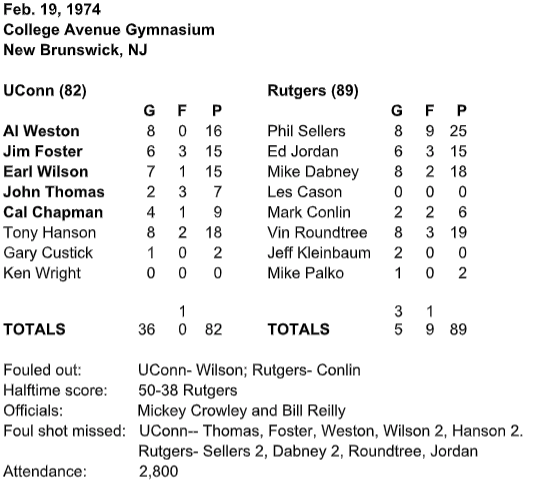

Box scores told the story

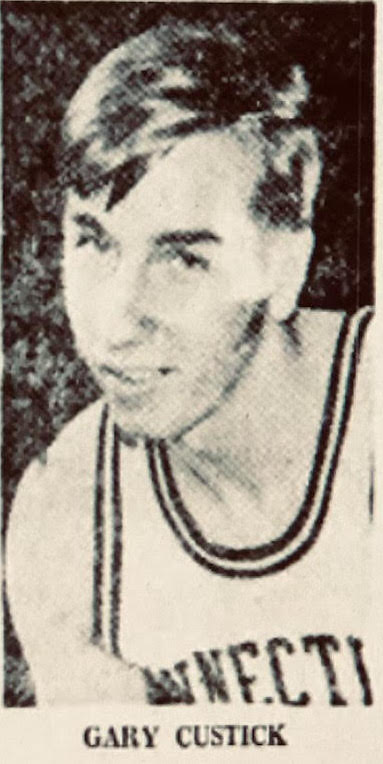

By downloading the box scores through the resources of newspapers.com, and with the assistance of Greg Stamos, a Connecticut attorney, former Ansonia H.S. player, and still a rabid basketball fan, we first eliminated the games in which 6-7 Gary Custic, a Caucasian, was a three-year starter. He was in the opening lineups until he and Calvin Chapman lost their starting roles “at midseason” (Bill Newell, Hartford Courant, Feb. 26, 1974.) Therefore, the hitherto unidentified game had to be prior to that date.

One of the problems we expected in this search was determining if the freshman, Tony Hanson, fit into the puzzle. We thought, as many UConn followers still do, that Hanson, who died unexpectedly in 2018, was an African-American and born in Waterbury CT.

Neither was the case. He told Don Harrison, author of “Hoops in Connecticut,” that he was born in Kingston, Jamaica, the same birthplace of Patrick Ewing. His mother was Chinese and his father was Jamaican. “I’m a mixture, predominantly Chinese. Most of my people are oriental,” were his words. Hanson and his mother moved to Waterbury when he was four.

There was another revealing reference in the Hartford Courant (March 2, 1974), in which Rowe was quoted as saying that earlier that season, when Custick was in the opening lineup, the first five were called “soul patrol plus one.” The obvious implication was that four Blacks and one Caucasian were the closest at the time for UConn to start a unit of only African-American players, as long as Custic was starting.

Two of the 1974 UConn team are deceased

Two of the 1974 UConn team are deceased

Regretfully, we must point out that Tony Hanson and Gary Custic are no longer alive. It is generally known that Hanson, who played in Europe, coached in England and was a mentor to handicapped kids in Connecticut, died in 2018 of a heart attack at 63.

What had not been known, even in Storrs, was the tragic fate of Custic, the team’s MVP in 1972.

For several weeks I have tried to trace his path since graduation in 1974. The athletic department and the alumni office had no knowledge. The four players I have spoken with were also without any information and had been trying to locate him for the past several years to invite him to their reunions.

I finally learned that over 30 years ago Custic experienced a terrible ending to his life. He was only 38 when he died on Aug. 30, 1990.

Game at Rutgers was what we were looking for

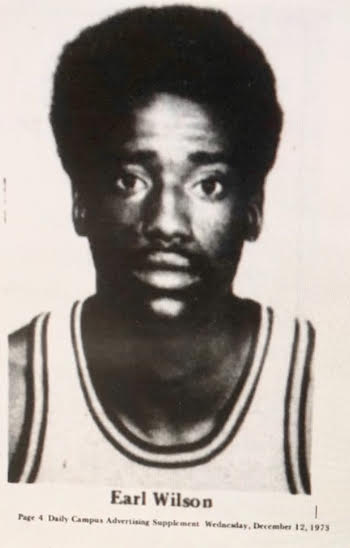

The game that Atty. Stamos and I ultimately hit upon with reasonable certainty as the first in which UConn started an all-Black quintet was played on Feb. 19, 1974. It was a road game at Rutgers in the College Avenue Gymnasium, New Brunswick, NJ. The unit consisted of Al Weston, John Thomas, Cal Chapman, captain Jimmy Foster, and Earl Wilson.

Those five had played the previous season with Alfonso “Al” Vaughn, Jr., who was captain of the 1973 team, and who graduated that year. Vaughn died in 2019 after a long illness.

The starters who made history

Al Weston All-State at Cromwell CT High School in 1972 and ultimately a successful coach there. He became a financial officer for the IRS. Weston is now retired and prepares income tax returns for friends.

Cal Chapman Jr. from West Haven CT where he still presumably lives. He first starred at Hopkins, a private school in New Haven. before entering UConn in 1969. Cal could not be reached by this writer or his former teammates. We have written to him at his last known address in West Haven but received no response. He is not on Facebook. Any help in contacting him would be appreciated (jkalaw@aol.com) so we can update this article.

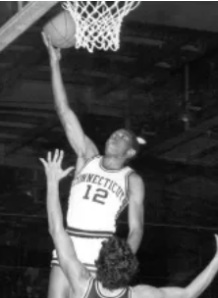

Jimmy Foster from Hoboken, NJ, was a football and basketball star in high school but gave up the gridiron after he broke a collarbone. Jimmy was the captain of the 1973-74 team and attended UConn after transferring from Becker Junior College. Coach Dee Rowe recruited him after a game against the UConn freshman team, led by Earl Wilson. Foster played in the American Basketball Association from 1974 to 1976 with the Spirits of St. Louis and Denver Nuggets. Following a contract dispute, he played briefly in Europe. After his pro career, he returned to UConn and earned a degree in business administration. Jimmy, who will turn 70 this December, is still an active insurance agent in Edgewater, NJ.

Earl Wilson a product of New Haven was team captain in 1975. He later converted to Islam and changed his name to Mustafa Abdul-Salaam. He graduated with a degree in Social Anthropology and received a master’s degree in Management and Economic Development from Southern Connecticut. Previously served as an executive director for the Upper Albany Neighborhood Collaborative in Hartford. Mustafa is currently facilitating a planning process in a black community (Ward 8) in Washington D.C. that is trying to combat gentrification.

John Thomas from Bogalusa, La, has been employed for the last 19 years in the financial department of Travelers Insurance in Hartford. He lives in Wethersfield CT, and returns to his birthplace twice a year.

After the season came the protests

On March 21, 1974, the season came to a close for the Huskies, when they lost in the final second to Boston College in the NIT. Meanwhile, racial unrest was heating up in Storrs. Exactly three weeks after elimination in the Madison Square Garden event about 300 of the 600 Black students on campus marched to Gulley Hall and presented university president Glenn Ferguson with their demands.

Feeling his response was too vague, they went ahead with a plan to occupy the library, which they did less than two weeks after that on April 23rd, to demand a meeting with the UConn head.

“A number of black students went into the library and had a peaceful sit in about fair treatment for the minority population” texted John Thomas, one of the basketball players who participated in the protest. He remembers that “state police from Danielson came and made an announcement that anyone who does not leave at that moment on their own free will would be carried out and arrested.”

Thomas left by way of the door but Jimmy Foster, the basketball captain, said “I jumped out of the window when I saw the police making arrests.”

They were physically removed

Starting at 7:30 AM police forcibly removed 219 protestors, many claiming they were physically and verbally abused.

The alliance said in a written statement they were “dramatizing our urgent need for a cultural center wherein we may study together and come together as a group unified in our ethnicity culture” (Bridgeport Post).

The following day state police appeared again and arrested 59 more students, mostly white, who were “showing their support for the black students’ demands.” (Bridgeport Post, UPI).

These taken into custody in the two days on charges of criminal trespass eventually had the violations dropped after the ACLU and NAACP got involved.

Thomas feels “it made some difference at the time but not a huge one. “I think it affected positive change for students later. I left when they made the announcement, so I didn’t get arrested. There were so many people. The younger generation, when they came along, didn’t have to fight so much for equal treatment because we paved the way for them.”

Back to Honey Fitch

We conclude by going back to Honey Fitch. He was on the varsity as a sophomore in 1933, before transferring to American International College in Springfield MA.

On Jan. 27, 1934, his team was in New London for a game with Coast Guard. As the players were warming up they were told Fitch could not play because more than half of the Academy’s students were from the South, and there had been a long tradition that no “negro” players be allowed to engage in contests there. After a long delay, the game started at 11 p.m. According to one account the coaches agreed to play with Fitch on the floor. In another, they decided that Fitch would sit out the game, which he did (newenglandhistoricalsociety.com).

“Evidently, something happened after the players left the locker room that induced Coach (John) Heldman to change his plans,” the Connecticut Campus wrote.

Coast Guard apologized, and Fitch played out the season. However, he was subjected to taunts and other displays of prejudice in most places the team visited.

The following year he transferred to AIC for economic reasons according to one of his two sons, Harrison Jr. (Brooks).

Before he died he sent Brooks to the University of Connecticut, essentially the same school he first attended though under a different name (Connecticut State Agricultural College). He graduated in 1964.

Keep in mind

Honey Fitch in 1933 and the five African American starting unit in 1974 were the beginnings of what has come to be not the exception at UConn but the rule.

And the almost simultaneous library demonstrations spurred activism dealing with racial conditions at UConn nearly at the same time as the milestone on the basketball court we have described.

Gone and Remembered

Those mentioned in this article, who are now deceased, are:

Bill Newell – 1977

“Honey” Fitch – 1984)

Gary H. Custic – 1990

Tony Hanson – 2018

Dee Rowe – 2021

Al Vaughn, Jr – 2019