- Zach Edey posted an easy double-double in Summer League debut. Here’s why he’ll succeed in NBAPosted 3 weeks ago

- What will we most remember these champion Boston Celtics for?Posted 1 month ago

- After long, seven-year road filled with excruciating losses, Celtics’ coast to NBA title felt ‘surreal’Posted 1 month ago

- South Florida men’s basketball is on an unbelievable heater– but also still on the bubblePosted 5 months ago

- Kobe Bufkin is balling out for Atlanta Hawks’ G League team. When will he be called up to NBA?Posted 6 months ago

- Former Knicks guards Immanuel Quickley, RJ Barrett may yet prove Raptors won the OG Anunoby tradePosted 7 months ago

- Rebounding savant Oscar Tshiebwe finally gets NBA chance he’s deserved for yearsPosted 7 months ago

- Is Tyrese Maxey vs. Tyrese Haliburton the next great NBA guard rivalry?Posted 9 months ago

- The Detroit Pistons are going to be a problem in a few yearsPosted 9 months ago

- March Madness hero, ex-Fairleigh Dickinson guard Demetre Roberts joins Austin Spurs’ G League training camp rosterPosted 9 months ago

John Thompson once took a high school team he coached off the court in protest over the officiating, yet it is rarely included as part of his legacy

- Updated: May 21, 2021

Before he made his legend at Georgetown, John Thompson was one of the best high school coaches in the country, though those in Connecticut may remember him for one particular incident.

By Joel Alderman

When John Thompson, the iconic former Georgetown Univ. basketball coach died on Aug. 30, 2020, the media was filled with deserving tributes and anecdotes about this mentor of mostly black youngsters, many of whom he steered away from potentially sordid lives. He was a civil rights advocate long before it was fashionable.

There were notable incidents he was known for, such as when he summoned notorious drug lord Rayful Edmond to his office and impressed upon him to stay away from his players.

Yet there was an event in his legacy that hardly anyone outside of Connecticut knows about. It was in a game in which he made an emotional and controversial decision to take his losing high schoolers off the court and get them home.

Whether he would have so acted during his 27 seasons as an illustrious college coach we can only guess. But at least we can describe that “lost weekend” for him and his team 51 years ago.

The St. Anthony Roman Catholic High School in Washington D.C., though small in size and enrollment, was a national basketball power through Thompson’s efforts. He brought his team to Connecticut in 1970 for back-to-back games against two of the state’s best.

Game #1

On the night of Feb. 20, 1970, they were in the farmland city of Colchester to face St. Thomas More, a private prep school in nearby Oakdale. The 16-1 Chancellors were coached by Nick Macarchuk, who went on to a 28-year college career at the helm of Canisius, Fordham, and Stony Brook and is now retired. It figured to be a hard-fought contest, and it was.

The home team trailed by one point at the end of the first quarter, then gradually pulled away to come out with a 76-69 victory. St. Thomas More had a good club, led by Cleve Royster who would play at Niagara. The team later defeated Dee Rowe’s Worcester Academy in the finals of the New England Prep School Tournament before losing to undefeated Columbia Prep of New York City in the Knights of Columbus tourney.

Among the spectators in Colchester were Bob Saulsbury, coach of Wilbur Cross High School of New Haven, and several members of its team. They were not there to be entertained. Since the Washington D.C. team would be playing Cross the following night, this was a scouting trip, an opportunity to see whether the Tonies were all they were cracked up to be.

According to Saulsbury, they were.

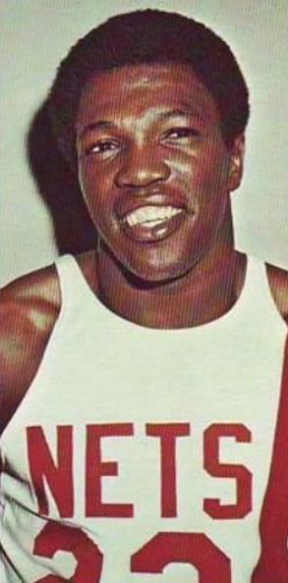

So they headed back to New Haven, a one hour drive thru rural areas, thinking about what they had seen. It was not as if they feared they would be outclassed. They were led by the late John Williamson, who would star at New Mexico State, then be a member of the New Jersey Nets’ two title winners in the ABA, and remain on the Nets when the league merged with the NBA.

Game #2

Just as Bob Saulsbury had been at the St. Thomas More-St. Anthony contest the night before, the coach of the Chancellors’ Nick Macarchuk, was at Cross to see this game. He remembers the scene to be described below involving Thompson, but his lasting impression was of the crowd.

“If the fire marshal was there he would have kept the attendance down. The gym was really overflowing with over 2,000 packed in.”

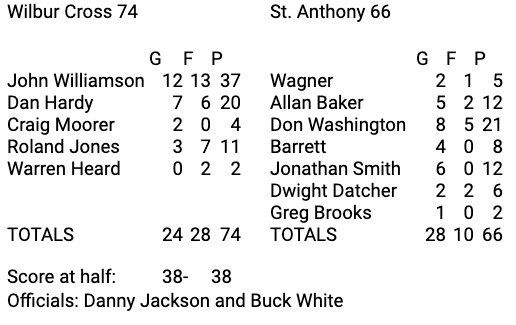

It promised to be a historic match-up played in what would be named in 2014 the Robert H. Saulsbury Gym. The Tonies, with a frontcourt standing 6-7, 6-6, and 6-4, established a 31-20 advantage in the second quarter and seemed ready to break the interstate contest open. But then the Governors hit on three long jumpers and Williamson tipped in a missed shot.

“Super” John, as he was known throughout his high school, college, and pro careers, tied the score on a pair of free throws. After St. Anthony went up again on a pair of foul shots by Don Washington, another future college and professional player, and now living in France, Williamson scored from down low and the score was tied at the half 38-38.

Third quarter

In the third period, both teams continued to run and shoot well. Williamson dominated for Cross just as Dan Hardy had sparked its second-quarter drive.

Fourth quarter

In the fourth quarter, Dwight Datcher of the Tonies stole an inbounds pass and went the length of the court to cut their deficit to 66-64. (Datcher passed away last year (2020).

After that, the Governors began to inch further and further ahead, with the help of Hardy’s three crucial free throws, and establish their largest lead of the night, with Williamson reaching 37 points and Hardy 20.

Meanwhile, the personals were piling up on the visitors and Thompson was not pleased with the officiating.

Williamson had made a sensational underhand layup and was low-bridged at the same time, tumbling to the court. Thompson felt that Williamson was charging but the officials said a St. Anthony player had bent over causing him to fall on his elbow and side.

The sudden end of the game

After a St. Anthony player threw the ball in the face of referee Edward “Buck” White a technical foul was called in addition to a personal. Thompson went onto the court arguing that his player did not do it intentionally. He continued to plead his case, and when he refused to go back to the bench another technical was rung up.

He persisted in objecting, even offering his wallet to the officials, as described by Paul Marslano in the New Haven Register and recently confirmed in my conversations with Saulsbury and Macarchuk. That display led to a third technical.

Williamson then went to the line for a one and one and three two-shot technicals. Cross was leading 74-66 with 2:47 left. As he was getting set to shoot the free throws Thompson waived his players off the court.

Super John never got to attempt those seven or possibly eight freebies. Nobody realized it immediately, but the game was over. Thompson, who had been a star at Providence College then the backup for Bill Russell on two Boston Celtic championship teams, brought his players into the locker room and eventually home to the D.C. area.

“I had to take my boys off the court before we were the laughing stock of the fans and the press. We never were in a one-and-one situation. We committed 31 fouls and they only had nine,” he explained later to Marslano, probably in an incredulous tone.

Sweating heavily, as he would be known to do during games, Thompson added, “I just can’t have my team face that type of officiating.”

Saulsbury, who will be 92 in August, remembers the episode vividly. He told me “I just couldn’t believe that a coach would do that because the officiating wasn’t going his way.”

It was a tragedy-struck group involved that night. At least three who played have died, John Williamson, Allan Baker, and Dwight Datcher. The official who was in the center of the controversy, Edward “Buck” White, also passed away after a long sickness in 2011.

I have not been able to locate Danny Jackson, the other official. At last report, he goes by his middle name, Daniel Wellington, and was a certified tennis instructor in Kansas City. Missouri. He had a school, Wellington Tennis Academy, If any of our readers knows of his whereabouts, we would appreciate being contacted (and you can do so by emailing the author at jkalaw@aol.com, ).

Bob Saulsbury is trying to contact the person he loaned his coaching records to a few years ago. These are of great value to him as he is preparing to write a book about his career. Bob cannot remember the person’s name, but if he is reading this article or anyone knows of the individual, please let us know, either by email or in the comments below.

So what was the final score?

Without a rulebook for 1970, we cannot say whether the game should have been considered a forfeit or if it was an official contest with the score remaining the same as when Thompson and his players pulled out.

Today, a referee decides a game is to be forfeited when a team refuses to play after being instructed to do so by an official. The forfeiting team then loses 2−0.

Failure to warn the team to resume playing and the team not compiling after 30 minutes shall cause the score when the action stopped to remain.

Whether Thompson was told by an official to resume play is not known. Unless and until we can contact Danny Jackson, it cannot be said. With all the confusion, emotions, and controversies, there may have been no such order.

So take your choice. Cross won either 74-66 or 2-0.

Who died and when:

John Williamson, 1996

“Super” John averaged 38.7 p.p.g. his senior year at Wilbur Cross H.S. in New Haven and was the first from Connecticut named to Parade Magazine’s All-American team in 1970, when he averaged close to 40 points a game. His one-leg, fall-away jump shots ignited home crowds that would chant “Supe . . . Supe . . . Supe.”

After high school he played at New Mexico State, was a member of the New Jersey Nets two championship teams in the former ABA, and was still on the Nets when the league merged with the NBA.

Lou Carnesecca, who coached the Nets from 1970-73 and who left to take over at St. John’s the year before Williamson went pro, recalled ”He was so strong and had such great tenacity. He was small, but he could score on practically anyone.” His brother James (Jiggy) Williamson was also a great player at the same high school.

James “Jiggy” Williamson (2005)

Member of Wilbur Cross’ undefeated 1974 team ranked No. 1 nationally, brother of Super John played at Univ. of Rhode Island usually with a toothpick in his mouth became a group home counselor a residential treatment center for adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems died at 49.

Dwight Datcher, 2019

Dwight Datcher graduated from Roger Williams College as its all-time leading scorer. He went back to St. Anthony as coach of the Tonies and compiled a 144-40 record. He then spent 30 years in athletic administration.

Allan Baker, 2010

Allan Baker was on the first Providence College team to reach an NCAA final four. He played for the Denver Nuggets and Utah Stars in the ABA. Earned a degree from Hartford Seminary School’s Black Ministers Program in 2008, two years before his death.

Edward T. “Buck” White, Sr, 2011

New Haven’s first Black official, Buck White received the Official of the Year Award from the Connecticut Basketball Association for 25 years of service. He was an honorary member of the New Haven Board of Approved Basketball Officials.

Paul Marslano, 2015

Veteran sports writer for the New Haven Register.

When last heard from

Finding out what has become of those mentioned in this article has been laborious and not necessarily current. We would appreciate any updated information.

Craig Moorer lives in Hyattsville MD, retired, worked for the child protection youth services and as a parole and probation agent for the Maryland Dept. of Public Safety

Roland Jones was living in Texas

Warren Heard moved to Baton Rouge, LA

Dan Hardy lives in the New Haven area

Danny (Wellington) Jackson, one of the two game officials, became a tennis pro and had his own school under the name of Wellington Tennis Academy in Kansas City MO

Don Washington

Washington lost his mother while in high school and Thompson became his legal guardian. He played part of one season for Dean Smith at North Carolina and averaged 21-plus points per game before he broke his foot. He joined the ABA’s Denver Nuggets and Utah Stars, then played out his career in France, where he still lives.

Jonathan Smith

Also followed Thompson to Georgetown in 1972. Had 20 against Arizona in the NCAA’s. Smith served in the State Department. He felt Thompson “taught me how to deal with life. . . (He) made me come to grips with life as a man.”

Greg Brooks

Another of the four from St. Anthony in Thompson’s first recruiting class at Georgetown, Greg Brooks was a solid sixth man off the bench for two seasons averaging 6.3 p.p.g. and finishing fifth in team scoring for the Hoyas.

Did John Thompson remember?

Although the lost weekend in Connecticut was not mentioned by the media in the various tributes to Thompson, and was omitted from his book of memoirs, “Out of the Shadows,” he apparently did not forget it.

Saulsbury had introduced his son, Robert Jr., to Thompson before the start of the St. Anthony-Cross game. Twelve years later, by which time he was a teacher and basketball coach at Ithaca (NY) Middle School, Robert Jr. noted that Georgetown was scheduled to play at Syracuse, not too far away, on Sunday afternoon, March 14, 1982.

He decided to take in the game. After Syracuse had upset the No. 8 Hoyas, they passed each other in a hallway and Thompson immediately recognized the younger Saulsbury. What he said was a classic.

“How are your cousins?” he asked.

One Comment